SIE 15 Dec 2021

[CW 25 Jan 2022: this is the accepted version. It is slightly different. The article is published. For the writing and publishing process see tag #SIE]

- Weßel, C. (2021). Social Informatics Experience: A Case Study on Learning and Teaching Sociological Basics in a Technical Context. Acta Informatica Pragensia, 10(3), 211–235. https://doi.org/10.18267/j.aip.170

Social Informatics Experience:

Learning and teaching sociological basics in a technical context. A case study.

Author

Christa Weßel [1]*

[1] Dr. Christa Weßel (freelance scientist, adviser, lecturer and author in organizational development, social informatics and higher education), Königstr. 43, 26180 Rastede, Germany; mail[at]christa-wessel.de

* mail[at]christa-wessel.de

Abstract

To be able to play an active role in the design, creation and development of a networked society students, scholars and practitioners need basic knowledge in social informatics. At a university of applied sciences students attended a one-term seminar that consisted of eight two-day workshops. The students learned and used theories, concepts and methods of social informatics (SI) focusing on the sociological part of SI. The learning and teaching approach is based upon competency-based learning. It enables students to explore a certain field. This is implemented by means of organization development, project-based learning, agile learning and teaching plus blended learning. It empowers teacher and students to work together efficiently, effectively and with joy. To learn how and why this approach worked, an embedded two-case case study investigated the design, implementation and evaluation of the workshop series. Finally the paper describes impediments to the communication and understanding of the term and the field social informatics and sketches ideas how to deal with it concerning study programs and the value social informatics can contribute to challenges like a pandemic.

Keywords

social informatics

socioinformatics

socio-informatics

project-based learning

continued multidisciplinary project-based learning (CM-PBL)

competency-based learning

agile learning

blended learning

organization development

case study

1 Education in SI

When did the digital era start? With the world wide web and the internet during the 1980ies and 1990ies? Earlier, with the astronauts and the men _on_ the moon? Whenever it started, the COVID-19-pandemic showed from its beginning in 2020 how useful and sometimes harmful information and communication technologies can be in the mastering of such a worldwide challenge. This relates to nearly all aspects: health care systems, government, education, public services, economics and of course the private life and physical and socio-psychological well-being of people. Communication in social media is of special relevance (Darius & Stephany, 2020).

Both is important: technology and social aspects. Social informatics (SI) strives to cover both. The science

SI can be broadly defined as a research field that focuses on the research of sociotechnical interactions at different levels in connection with the development of the information society, including the social aspects of computerization and informatization, which can be structured into three main areas: interactions between ICT and humans, ICT applications in the social sciences, and ICT applications as a social sciences research tool.

(Smutny & Vehovar, 2020, p. 537)

In a broader context for the daily life of social informatics I propose the following definition of SI, translated from (Weßel, 2021a, p. 20-21).

Social Informatics deals with the interrelationship of information- and communication technology and social change. This affects individuals, groups, (international) organizations (companies, public authorities, associations et cetera) plus local communities, states and international communities of states.

The task of social informatics is to support by research and development the design, implementation and maintenance of information systems for the benefit of individuals, groups and society, so that those, who develop, build, sell and maintain these systems, tailor technology to people and not inverse. To afford this social informatics builds upon disciplines like sociology, psychology, philosophy, anthropology, historical sciences, economics, law and - of course - computer sciences.

Especially the world wide web and the internet have a lasting effect on our daily life: web 1.0 (static data presentation), web 2.0 (the reader turns into player, for instance in social media), web 3.0 (semantic) and the internet of things, internet 4.0.

To be able to play an active role in the design, creation and development of a networked society students, scholars and practitioners need basic knowledge in social informatics.

Interesting education programs and materials stem from the United Kingdom, Russia, South Africa, Slovenia, the United States and Germany. Research Institutes in Scotland, Germany, Russia, Italy and the Middle East focus on social informatics. Smutny and Vehovar (2020) identify five to seven schools of social informatics distributed worldwide. The particular scientific scope affects the design of study programs and the diversity of contents. One of the early study programs in social informatics was implemented in Slovenia. The Faculty of Social Sciences at University of Ljubljana (2021) offers since 1984 a study program in social informatics (Smutny, 2016).

In Germany the term social informatics is not widely known. Computer scientists speak about "Informatik und Gesellschaft", information technology and society. Since decades this topic is part of curricula in computer sciences. The 2000 and 2001 lecture topics of Professor Wolfgang Coy at the Humboldt University Berlin are a fine example (Coy, 2000). In my view the headlines are with minor adaptations still applicable in a today seminar on social informatics. Only a few universities in Germany offer a particular degree program in social informatics, for instance the University of Kaiserlautern. The university calls the bachelor and master programs "Socioinformatics" (TU Kaiserslautern, 2021).

Another approach is to focus in a study path on social informatics (HFU, 2021). From 2015 on the Hochschule Furtwangen, University of Applied Sciences (HFU), offered a SI branch of study in the bachelor program "IT product management". The study program included during the fourth term two modules on social informatics, "Informatik im sozialen Kontext" (information technology and its social context) and "Soziale Netze" (social nets). The modules combined lecture and seminar. During summer term 2017 and winter term 2017/2018 a visiting lecturer was hired to perform these modules. With the consent of the university she merged them in the workshop series "Sozioinformatik". This was her answer to the question "How can students learn about SI?" To provide a high quality she performed an attending study as participating observer: as teacher and as researcher, performing the study "Social Informatics Experience: Learning and teaching sociological basics in a technical context" (short: Social Informatics Experience). From here on I report and reflect in the first person. The paper is written in a personal style as Stake advocates it (Stake, 1995, p. 135).

Based upon findings, that competency-based learning enriches the students learning success and satisfaction (Jones et al., 2002), and upon the development of continued multidisciplinary project-based learning (Weßel & Spreckelsen, 2009) plus former experiences with the transfer of CM-PBL to seminar settings (Weßel, 2010 & 2015), I assumed, that the CM-PBL approach can be transferred to a workshop series setting, that agile learning and teaching support this, and that students' commitment, success and satisfaction is high in this setting.

The aim of this paper is to answer the research questions "How can the concepts of continued multidisciplinary project-based learning (CM-PBL) and agile learning and teaching (ALT) transferred to a one-term-seminar-setting in social informatics?" – "Does it work?" – "How does it work?" – "Why does it work?" – "What is necessary to make it happen?" The study should answer especially the "How"-questions to offer interested colleagues, students and other stakeholders in learning and teaching, like university managers, an example and perhaps inspiration for their own work. The learning and teaching approach described here is not restricted to SI. It can be used for other topics and fields. The design of the seminar as workshop series, the data and the conclusion are intended to be used and perhaps useful in further research, decision making and application especially in the multi- and trans-disciplinary field of social informatics.

The paper is organized as follows. After a short description of some didactic basics, "Learning and Teaching", which are elaborated in Appendix A, the method "Case Study considering Action Research and Triangulation" is outlined with immediate references to the application in the study "Social Informatics Experience". The section "SI Workshop Series" presents the results of the study. The final subsection of the results contains a students' design for a study program for social informatics. This builds the transition to the discussion and the conclusion.

2 Learning and Teaching

Students need a comprehensive education in subject-specific, methodological and social competencies and skills. Learning in realistic scenarios is based upon the theory of cognitive learning: learning by insights and on a model empowers the learner, to explore a topic autonomously, to use scientific methods and to develop solutions. This enhances the learner's motivation and improves the learning outcome short-, middle- and long-term (Felder et al., 2000; Slavin, 1996). Teachers envision themselves as facilitator, mentor, guide (Weßel & Spreckelsen, 2009). The purpose of competency-based learning (CBL) is to empower students to develop these skills (Jones et al., 2002). Several studies and experiences during the last decades show that CBL and its realization by approaches, like project-based learning (PBL) and continued multidisciplinary project-based learning (CM-PBL), empower students to learn efficiently, effectively, with joy and holistic (for instance Felder et al., 2000; Weßel & Spreckelsen, 2009). This is enriched by the application of agile learning and teaching (ALT) and blended learning (BL). Appendix A describes these theories, concepts and approaches in some detail.

As I am an organization developer I use theories, concepts and methods of organization development (OD). The goal and purpose of OD is to pilot change for the well being of both the organization and the people inside and beyond (Argyris & Schön, 1978; Cooperrider et al., 2008; Cummings, 2008; DeMarco & Lister, 1999; Laloux, 2014; Senge, 2006; Sennett, 2012; Wiegers, 1996). OD can be applied transorganizational, organizational, in a department, in projects and other settings, where ever people act together. Transferred to the implementation of a seminar this means, that a teacher as the OD manager in charge adopts this attitude and integrates students – the OD staff – and the administration of the university and colleagues – OD staff and management – into the design, planning, management and realization process of a particular seminar. The students' salary is their learning, success and certificate. Appendix B describes some basics of OD.

3 Case Study considering Action Research and Triangulation

The study "Social Informatics Experience" was performed as case study, because there were two workshop series and foremost, because case studies strive to understand, get new insights and to answer how and why something happens as it happens and how and why something works (Stake, 1995, p. 1; Yin, 2018, p. 2). The case study approach uses especially qualitative research methods and in certain designs also quantitative methods (Scholz & Tietje, 2002, p. 14). It strives to take into account triangulation. The researcher can either be only an observer or both, researcher and participant. In the study I acted as researcher and a participant, the teacher. The students are in so far also researchers as this study follows Lewin's action research (Lewin, 1946). The following sub-sections describe the methods and their application in the study.

3.1 Case study

A case study takes place in the field. Field means to perform a study not in a laboratory but in the "real" world. A case is a defined unit, that can be explored and analysed. Case studies are used in education and research. In research the purpose of case studies is to gain insights, to understand, to develop theories, models, concepts and hypotheses and – depending on the design – to test a hypothesis. The dimension and classification of case studies can be described by the aspects design, motivation, epistemological status, purpose, data, format and synthesis (Scholz & Tietje, 2002, p. 10). There are four basic case study designs, that can be sketched on a 2x2-table (Yin, 2018, p. 48). One dimension is the number of cases: single or multiple. The other dimension is the number of analysed units. A holistic case study has one unit. If more than one unit in a case is analysed, it is an embedded case study. The steps of a case study are, to define the research questions and the case(s), to sketch the research process and to perform the data collection, analysis and conclusion.

The study "Social Informatics Experience" is designed as an embedded two-case case study. The units of the cases are "students (socio-demographic attributes)", "commitment", "success" and "satisfaction". The two editions of the workshop series build the two cases: case 1 in summer term 2017; case 2 in winter term 2017/2018. The motivation is both intrinsic and extrinsic. Intrinsic: the researcher is similarly the teacher and is interested in the well-being of the students and success of their learning. Extrinsic in so far as that the design of the seminar as workshop series, the data and the conclusion can be used and perhaps useful in further research, decision making and application. The epistemological status is explorative, descriptive and explanatory. Explorative, to learn whether such an approach is possible in such a setting. Descriptive by the use of the concepts of PBL and agile learning and teaching. Explanatory formulating of the hypothesis, that students will learn more efficiently, effectively and with more joy than in other "classical" settings. The purpose of this study was action/application. The data were both qualitative and quantitative. Here is to consider that the quantitative data are to be seen as part of the description without any statistical tests. The study's format is structured with three phases of data collection and by the design of the seminar as workshop series. The synthesis, this is the knowledge integration, is based upon the analysis and the interpretation of the collected data with awareness of "classical" learning settings. The synthesis is elaborated in the discussion and in the conclusion and outlook.

3.2 Action Research

The student knows the answer. This sentence is inspired by the approach "the client knows the answer", attributed to organization developers like Kurt Lewin, Chris Argyris and Donald Schön. Kurt Lewin (1890–1947) coined the term Action Research in the 1940ies. His research and work as a consultant for companies and the government and work with the people in these organizations focused on group dynamics and change. Lewin became aware that only the cooperation of scientists and practitioners offer relevant progress and new insights: "Socially, it does not suffice that university organizations produce new scientific insights. It will be necessary to install fact-finding procedures, social eyes and ears, right into social action bodies." (Lewin, 1946, p. 38).

He defined three steps: "planning, executing, and reconnaissance or fact-finding" (ibidem, p. 38). Scientists and practitioners perform these steps together. This approach answers four purposes: evaluation, to check, whether the intended goals are achieved; learning, to win insights on the strengths and weaknesses of an action or method; gaining material for both the planning of next steps and for revision or redesign. In the study "Social Informatics Experience" the practitioners were the teacher, the university administration and the students. The teacher designed the workshop series, all practitioners were involved in the planning and the evaluation, the students and the teacher performed ("executed") the workshop series. The approach was formative. During the preparation and execution of the workshop series the teacher and the students evaluated and adapted the workshop sub-topics to the needs, questions and suggestions of both, the students and the teacher.

3.3 Triangulation

Qualitative research is characterised by openness, explication, subjectivity, reflection and interpretation (Strauss & Corbin, 1998, p. 7). It is an iterative process, which is maintained until saturation is reached. Qualitative studies are performed incrementally. The researcher goes into the field to learn about people, their life, their work, their needs and their ideas. The data collection is for example performed as observation or interview and relies on textual formats. The high quality of the research is assured by triangulation (Ammenwerth et al., 2003; Stake, 1995, p. 107-120; Yin, 2018, p. 127-129). This means to work with different sources of data, methods, observers and/or theories. The study "Social Informatics Experience" meets three of these.

The methods are both qualitative and quantitative. The qualitative research methods include here observation, interviews and the analysis of text documents (students' portfolios, teacher's blog, university's website). Descriptive quantitative data and numbers stem from the university's website, the cases and the evaluation questionnaire in case 2. There are several data sources gained by the exploration of different units in the university context and the two cases. The observer (researcher) was just one, thus this criterion of triangulation is not fulfilled. The study uses several theories and suppositions. These are competency-based learning, action research and organization development. Competency-based learning fosters students short-, middle- and long-term learning success in professional and social skills. Action research is characterized by the close cooperation between researcher and the actors in the research object. Organization development is in turn based on theories, insights and methods from sociology, psychology, economics and didactic.

4 SI Workshop Series

This section reports upon the results. It starts with the research questions, the data and the setting, "Getting started". The workshops series follow with "Topics and contents" and the series/cases 1 and 2. The workload is described for both cases together, as there are strong similarities. A students' design of a study program for social informatics builds the transition to the following section, the discussion.

4.1 Research questions

The study attended the workshop series. This should afford to reach a high quality in the development, performing and evaluation processes. Based upon findings, that competency-based learning enriches the students learning success and satisfaction (Jones et al., 2002), and upon the development of continued multidisciplinary project-based learning (Weßel & Spreckelsen, 2009) plus former experiences with the transfer of CM-PBL to seminar settings (Weßel, 2010 & 2015), I assumed, that the CM-PBL approach can be transferred to a workshop series setting, that agile learning and teaching supports this, and that students' commitment, success and satisfaction is high in this setting. This led to the following research questions:

"How can the concepts of continued multidisciplinary project-based learning (CM-PBL) and agile learning and teaching (ALT) transferred to a one-term-seminar-setting in social informatics?" – "Does it work?" – "How does it work?" – "Why does it work?" – "What is necessary to make it happen?"

4.2 Data

Data were collected from November 2016 until January 2018 in three phases: context (the university), workshop series/case 1 and 2. Qualitative data stem from observation, short group interviews (check-in/check-out on every workshop day), focus group interviews (workshops 5 & 8 in case 1) and texts (students' portfolios; own blog entries). Quantitative data include the description of the university on its website, the number of workshops and teaching units, number of students, rate of participation and success in the proofs of performance and also the workload for both students and teacher. The quantitative data are descriptive without further statistical tests.

4.3 Getting started

Hochschule Furtwangen University (HFU) is located in the southwest of Germany (HFU, 2021a). About five thousand students are enrolled in bachelor and master programs. One of the bachelor programs is "IT Product Management" with the major fields either software processes or social informatics (HFU, 2021b). It started in the winter term 2015/2016 and included during the fourth term in 2017 and 2017/2018 two modules on social informatics, "Informatik im sozialen Kontext" (information technology and its social context) and "Soziale Netze" (social nets). To consider is, that meanwhile the contents of the study program changed. Thus the reader will not find the description of the modules in 2017 on the current website of HFU, but they are online available via (Weßel, 2018). The first run had to take place during summer term 2017. At this time 121 students were enrolled in the study program "IT product management". Twelve of them, four women and eight men performed the fourth term. They were the first, who had enrolled in 2015.

On November 29, 2016, I got an e-mail from a professor at HFU. They were looking for a visiting lecturer in social informatics. He found my blog section on social informatics and decided to ask me whether I was interested in teaching the SI modules during the summer term 2017. During our phone conversation one day later he also asked me to take part in the staffing procedure of a professorship in social informatics in January 2017. I accepted both. Although I wanted to stay a freelance lecturer I knew that this procedure would be a good opportunity to become acquainted with the university and some colleagues, students and members of the administration, especially the office assistants of the department of informatics, two month ahead the semester.

The two modules covered overall 120 teaching units (each 45 minutes). The university accepted my proposal to merge them and to design and implement a setting with eight workshops (each two days) and two proofs of performance. The design started with questions on "What is social informatics?" I published the questions and a sketch of the proofs of performance in my blog on February 24, 2017, and discussed them with colleagues and former students (Appendix C). This led to the identification of the workshop topics, considering and integrating the requirements and contents, the university had included in the description of the modules.

The continued support of the two office assistants of the department of informatics from the beginning in January 2017 until the finish in January 2018 was crucial for the success. Furthermore the students were involved. I sketched the structure and together we decided during the first workshop on aspects like time tables for the proofs of performance plus the organization of the e-learning part of our work, using platforms for documentations and files and the communication via e-mails. During the terms we adapted the topics and the time table if the students or I asked for changes.

The workshops took place on Thursday and Friday every two or three weeks, starting at noon on Thursday and finishing on Friday afternoon. The breaks during the workshop days did not follow a strict timetable, only lunch was fixed: one hour, starting mostly at 12:30. For the shorter breaks everyone was in charge. I had to keep in mind the need for breaks. The students had to announce the need for a break – if I forgot it. The seminar room of the department of computer science was large, about 15 m long and 12 m wide, overall about 180 square meters. Thus we could put some tables aside to gain space for work in the room, for instance the check-in/check-out.

We evaluated the satisfaction of both, students and teacher, formative during the workshops in the check-in/check-out and in dialogues. This afforded to adapt the learning and teaching process and procedures in course of the workshop series. Summative the students described their experiences with the workshops, new insights and grade of satisfaction in the portfolios. I reported about my reflections and grade of satisfaction as teacher in the blog "social informatics" (Weßel, 2021b) and in a book on learning and teaching (Weßel, 2019, p. 261-264).

4.4 Workshop topics and contents

The objective was to empower students to use theories, concepts and methods from social informatics for their work as IT product managers. They shall be able to take social, political and technical preconditions into account and to be aware of the social and ecological responsibility of IT product managers. As the technical aspects were objects of other modules the workshops focused on the following topics:

- Getting started: Social net and electronic media.

- Exploration and evaluation: What do the users need?

- Internationalization and globalization: Life is a net.

- Product management and ethics: The art of balance between the technically feasible and social consequences.

- Life world and work world: In fact I live while I work.

- Hackathon: Let's work … and have fun.

- Digital Dexterity and Internet of Things: About handling the new.

- Synopsis: It's all about communication.

Further topics were definitions in informatics, sociology, economics plus group dynamics and team work, network-, organization- and stakeholder-analysis, innovation, digital dexterity, agile management and appreciative inquiry.

The complete curriculum is available for students and the public in German since 2017 and also in English since December 2021 (Weßel, 2018). Appendix C gives an overview on the online curriculum with its topics such as introduction, contents and learning objectives, workshop series, proofs of performance and literature recommendation.

The students worked on proofs of performance in teams of two or three students. The proofs were related to the primordially two modules, that were merged in the workshop series. For "social nets" the students wrote a paper concerning a small students' research project on topics like smart city or digital dexterity. The proof of performance for "information technology and its social context" was the creation of a portfolio. It had to contain several reflections on topics like ethics and a description of the tasks the students worked on during the workshops. The students presented their progress in each workshop and got feedback from their peers and from me, the teacher. Milestones of the proofs of performance are: building the small team, finding and describing the topic, literature, development, final questions (to the peers and the teacher), delivery and review. Appendix D offers some details on scope and procedure.

We, students and teacher, worked together using the approach of agile learning and teaching (see Appendix A.3 for more details).

4.5 Case 1: summer term 2017

The workshop series started on March 30 & 31, 2017, and finished with the eighth workshop on June 22 & 23, 2017.

4.5.1 Students

Five students enrolled, four men and one woman. Four of them were in their early twenties, one man about ten years older. All of them were born in Germany, two had an international background, their families coming from south-east Europe and the Middle East. Four of them had a job to make a living, at least partly. Other financial resources were parents. During the first workshop they described their motivation to enrol in the study path social informatics for instance as "less technical stuff than in the other study path" and their interest in the social aspects of computer technology, information systems and digitalization.

4.5.2 Commitment

All five students took regularly and actively part in the workshops. They communicated with their peers and with me (the teacher) the reasons, if they could not show up. The reasons were job obligations, illness, respectively family matters. The students worked actively and reliably together on their proofs of performance. One student engaged himself thoroughly to manage the participation in the workshop series. Due to relays in former terms he had a big workload of more classes than usual. First it seemed, that he would not be able to take part, but as he told us during the third workshop: "I really want to take part, because this workshop series is special and I do not want to postpone this for another term." Later we learned, that, if this student would have left, we would have had to cancel the whole workshop series, as the university requested at least five participants. All of us, his peers and the teacher, were grateful, that he sorted it out to take part.

4.5.3 Success

The students worked on proofs of performance in teams of two, respectively three students. The students' research topics were "How can we convert Furtwangen to a smart city?" (Wie können wir Furtwangen zu einer Smart City machen?) and "How can the marketing for a print medium take place in the digital era?" (Wie kann das Marketing für ein Print-Medium im digitalen Zeitalter erfolgen?). All five students succeeded and got good grades in both the students' research projects (one A, one B) and the portfolios (three A's, one B, one C).

4.5.4 Satisfaction

The students' answers during the check-in on the first day of the fifth workshop induced a dialogue on the unfamiliar learning and teaching approach.

Workshop 5:

Now at half-time of the workshop series – five of eight are done – we draw up an interim balance. The learning setting is new in so far, that CM-PBL requires and fosters the cooperation in between the face-to-face learning days. One principle is: "Do not muse on a problem more than two hours (for instance in Software-Development). Then you ask us in the forum or your buddy or an expert in our team or outside, who can help you."

We use the buddy system in the portfolio and in the students' research projects. Still it is unfamiliar for the students, not just to do their task for the next face-to-face learning, but to confer with their buddies, for instance on reflections in their portfolios, to ask for and to give feedback and to discuss questions.

[…]

The students are pleased with our learning approach with dialogues, group exercises, visualizations and the analysis of movies with reference to IT product management and social informatics. Unaccustomed and thus – still – requiring some effort is the project setting. This requires, that the students do not perform a final sprint during the second half or later up to the end of their term, but to work from the beginning on – "continued" – on their proofs of performance, the portfolio and the students' research project.

(translated from the blog of 2017, May 8 - https://www.christa-wessel.de/2017/05/08/ich-lebe-auch/)

Summative the students offered insights on their experiences with the workshops, new insights and grade of satisfaction in their portfolios.

bachelor student IT product management, early twenties:

Now we look on the closing words of the portfolio. They show my personal conclusion, describing my reflection on the semester overall, during which I attended the workshops in the modules "Social Nets" and "Informatics and Society". I liked the workshops overall although I'm not a person who likes to interact and to occupy centre stage. Alas I could not avoid this as our group consisted of just five students and the teacher. Overall this evolved as positive, because the workshops were everything but not a boring lesson and indeed I had fun. The continued repetition of the subject matter lingered in the memory. Beside this I reflected intensely on my studies in IT product management and its parts. The flexible working style, for instance the organization of breaks and lessons was relaxing and precious. In the beginning my own learning targets were indifferent and not well defined. During the semester I was able to shape and to reach them. Beside this the inclusion of and work on topics apart from social informatics stemming from other modules were excellent. For instance we looked on quality management, feedback and presentations techniques. Summarizing I can say with good conscience that I have performed successfully the modules "Social Nets" and "Informatics and Society".

(author's translation of the student's portfolio written in German)

During the final workshop we, students and teacher, performed a summative, qualitative evaluation. We used questions otherwise in use for the evaluation of a consulting project with two perspectives (Weßel, 2017, p. 247-248): (a) the client and customer, in our case the students, and (b) the service provider, this is the consultant or IT product manager, in our case the teacher, for instance:

- Objective achieved, assessment based upon in advance defined criteria.

- Balanced budget (here: time, effort).

- Learned something new.

- Satisfaction, assessment based upon in advance defined criteria.

- What was good? And why?

- What was not good? And why? And how to improve?

- Client: can we proceed alone? Without the service provider?

We saw the goals of the workshop series met and were satisfied. The quality of our work together in the small teams and in the large group of students and teacher we assessed between 7 and 8.5 on a scale of 1 to 10.

4.6 Case 2: winter term 2017/2018

The workshop series started on November 2 & 3, 2017, and finished with the eighth workshop on January 18 & 19, 2018.

4.6.1 Students

Eleven students enrolled, all male, age between early twenties and early thirties. The cultural background was mixed. Some were born in Germany and their families coming from Germany (about half of the participants), some were born abroad and they and their families migrated to Germany and some were born in Germany and their parents or grandparents had come to Germany. The countries were located in the south-east of Europe and Middle East. Several students had a job to make a living, at least partly. Other financial resources were parents. The students described – similar to the students in case 1 – during the first workshop their motivation to enrol in the study path social informatics for instance as "less technical stuff than in the other study path" and their interest in the social aspects of computer technology, information systems and digitalization.

4.6.2 Commitment

The attendance rate was as follows. Ten students missed three to six of the sixteen workshop days. They communicated with their peers and with me (the teacher) the reasons, if they could not show up on a day or during a whole workshop. The reasons were job obligations, illness, respectively family matters. One student missed seven of the sixteen workshop days. In the beginning he offered no reasons to his peers or to me. I intervened in a one-to-one conversation during the third workshop and reminded the student that not only for him, but also for his peers in the proofs of performance the participation in the workshops was crucial for their succeeding. The other ten students worked actively and reliably during the workshops and on their proofs of performance.

4.6.3 Success

In the students' research project three of the four teams succeeded with a B. One group failed and got an F. The students' research topics were "Digital Dexterity" (Digitale Geschicklichkeit); "Marketing for a musician and his media in the digital era" ("BLCK4EST.REC" Vermarktung eines Musik Artist – und seines Mediums im digitalen Zeitalter); "Social nets as marketing media for the selling of mobile phones" (Soziale Netze als Marketingmedien für den Verkauf von Mobiltelefonen) and "Gaming" (Gaming). One student failed with an F in his portfolio. The others succeeded: three A's, six B's and one D. The student, who failed in both the portfolio and the students' research project, was the student who missed seven days of the workshops. The peers of this student in the students' research project could not compensate his low commitment. On the final day of the last workshop they expressed their understanding of my obligation to assess the group's work. In advance, before I graded this students' research project with an F, I consulted with the head of teaching in the department of informatics. He confirmed that I had to take this route.

4.6.4 Satisfaction

After the eight workshops the eleven students filled in an evaluation questionnaire of the university. Both in the descriptive statistical part and in the qualitative part the students described their satisfaction with the quality of the teaching and their own contributions as high and their workload as appropriate. Furthermore the students described their experiences in the portfolios.

bachelor student IT product management, early twenties:

What was extraordinary during these workshops, one was asked during our tasks to think for ourselves and not always to use the internet. Thus one should be able to gain independence from digitalization, otherwise one would go daft.

(author's translation of the student's portfolio written in German)

bachelor student IT product management, early twenties:

The reflection overall becomes my final words in this portfolio, to be read as conclusion. Here I go into the workshops and not into the contents of the portfolio so far. Through these workshops I became acquainted with a new way of learning. The workshops so far are very good structured and brought more fun than any dry lecture or seminar. Thus time passed by remarkable faster, because we moved a lot and one had always something to do. Beside this I like a lot, that movies can bring us important insights, because this brought modern methods to the fore. The reflection of the peers [*] during the first part of a particular workshop on the topics of the previous workshop I see as a useful method, because more than expected is kept in memory.

In addition I gave thoughts to my study program "IT product management" and I faced intensely up to its components. Furthermore I appreciated the conjunction of social informatics with the problems, questions or tasks from other modules of this term, for instance certain components like leadership and team building […].

Concluding I can say, I won a new repertoire of knowledge and I discern in my case a constant learning process.

(author's translation of the student's portfolio written in German)

[*] reflection of the peers: Two students discuss with the others the topics of the previous workshop, using anything but a presentation. Often they developed and used special quizzes and other games. This takes about twenty to thirty minutes and follows the approach "learning by teaching".

4.7 Case 1 and 2: Workload

The Bologna approach expects 25 to 30 hours per credit (European Commission/EACEA/Eurydice, 2020, p. 10). 60 credits correspond to a full-time-equivalent academic year, 1500 – 1800 hours. The workshop series covered two modules with 90 hours face-to-face learning (contact hours) and expected 270 hours self study, resulting in 12 credits. This corresponds to 30 hours per credit.

The students in case 1 and case 2 described their overall workload including the proofs of performance as slightly higher than in other seminar settings, but adequate. The students reported in contrast to traditional approaches a different dispersion of their workload during the term (see paragraph 4.5.4 "Satisfaction").

The teacher's workload as a visiting lecturer comprised the preparation, realization and post processing of the teaching and also the reviews of the proofs of performance and the communication with the administration of the university. During my projects I keep a logbook with the dates, events, work done and the hours spent. The teaching units in each term were 120, each 45 minutes. This matches 90 hours. In case 1 my workload was 238 hours, this corresponds with 2 hours per teaching unit. In case 2 it was 129 hours, this means 1.1 hour per unit. The larger amount of workload during case 1 is related to the design of the seminar with its workshops and to the detailed documentation of the workshops in the blog, publicly accessible for the students and other interested people. During case 2 I did without a detailed documentation in the blog and referred the students to the blog entries of the previous term, as the content of the workshops were similar. The overall workload was 367 hours for 240 teaching units. The rate 1.5 hours working load per teaching unit corresponds to former experiences in first and second runs of a seminar. Other freelance lecturers (visiting lecturers) told me, that their workload was similar, sometimes higher for the first and second run of a seminar.

What is not included, but of course done and thus to add, is the time to keep up with the discipline social informatics. I tried to find recent surveys and studies on teachers' workload and faculty's workload, in vain. Perhaps I failed in my research or the topic is not of peculiar interest. Nevertheless I would like to recommend the University of Dayton "University Faculty Workload Guidelines" (2011). It is a holistic overview and puts also emphasis on the need of continued teacher's learning: "A faculty member who is teaching twelve semester hours per semester can be expected to spend at least an additional twenty-four clock hours in teaching-related activities, including keeping up with her/his discipline." (University of Dayton, 2011, p. 6; p. 2 in the PDF).

4.8 A study program for social informatics: students' design

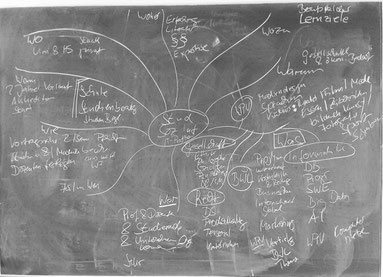

On June 23, 2017, during in the final workshop of case 1 the students developed a study program for social informatics. The leading question was: "What should students learn and how would you implement it?" The students used the 8+1 W questions and sketched a mind map. The 8+1 W questions comprise (Weßel, 2017, p. 33-40): What for? objective; Why? motivation and cause; What? contents and tasks; Who? roles and functions; for Whom? target group, client, customer; hoW? methods; When? timescale and appointments; Where? places; and Where from? data, information, theories, models, concepts, publications, reports, documentations, contact persons.

(Future) students and other stakeholders, like the administration of universities, teachers, education authorities and companies build the target audience. The students put emphasis on the topics and classes for the fields informatics, economics, sociology and elective subjects. Especially elective subjects offer the opportunity to think outside the box and to learn together with students and teachers of other study programs and departments and with experts and organizations beyond the bounds of the university, for instance with an artist, a restaurant or a magazine publishing house. In the sense of user-oriented software development the students voted for the inclusion and cooperation of all stakeholders from the very beginning of the design and implementation of a study program: students, teachers and the administration of a university.

5 Discussion

Social informatics is an emerging and important field in the digital era (Smutny, 2016; Smutny & Vehovar, 2020). Thus students need training in the topics, in scientific and other professional methods and the opportunity to consolidate and expand their social skills (Smutny, 2016; Weßel & Spreckelsen, 2009).

The topics of SI can be differentiated in technical and sociological parts (Smutny, 2016; Smutny & Vehovar, 2020). The workshop series presented in this paper covers two modules for students in the bachelor program "IT product management" of HFU. It focuses on the sociological aspects of social informatics. The learning and teaching approach is based upon the theories and concepts of competency-based learning (CBL) and uses concepts, methods and tools of continued multidisciplinary project-based learning (CM-PBL), agile learning and teaching (ALT) and blended learning (BL). Agile working methods like Scrum were adapted to the needs of students and teacher during a workshop series with two proofs of performance. (References on CBL, CM-PBL, ALT and BL see above, section "Learning and Teaching", and Appendix A "Learning concepts".)

The questions that occurred were "How can the concepts of CM-PBL and agile learning and teaching transferred to a one-term-seminar-setting in social informatics?", "Does it work?", "Why does it work?", "What is necessary to make it happen?" Case studies can answer how and why questions striving for a deep understanding, using qualitative and quantitative methods and considering the four principles of triangulation in methods, data sources, researcher and also theories and suppositions (Ammenwerth et al., 2003; Stake, 1995, p. 107-120; Yin, 2018, p. 127-129). The study "Social Informatics Experience", performed by one researcher, triangulates in methods, data sources, and also theories and suppositions.

The study showed a high commitment, success and satisfaction of the students and an appropriate workload for both students and teacher. Three conditions built the basis for the success, each mandatory: the context at the university, the participating students and the background of the teacher.

The staff of the university was open minded for the introduction of a new learning and teaching approach. The head of department of informatics, the head of teaching, other professors and the office assistants of the department of informatics aided the teacher, a visiting lecturer. The fact, that the modules "Informatik im sozialen Kontext" (information technology and its social context) and "Soziale Netze" (social nets) had their first run in the new study program "IT product management" may have fostered this.

A further component of the context is the learning environment. The layout of rooms and houses is very important for human well-being and thus their work (Hall & Hall, 1975; Hundertwasser 1985/1991). The university provided for the workshop series a large and well-lit room with windows on both sides, which could be opened and allowed to air thoroughly. The large room of about 180 square meters afforded to work not in the classical desk row with chalk and talk technique but to adapt the positioning to a large refectory-like table where all could be seated plus further tables for group work and to win space for work in the room, for instance standing in a circle during the check-in and check-out. Furthermore large blackboards for the visualisations also helped to avoid paper and pencil waste. As virus concentration and thus risk of infection is higher indoor (Buonanno et al., 2020), one of the prevention measures during the COVID-19 pandemic is airing the rooms. The WHO offers a roadmap with an extended glossary and scientific references, what and how it can be done (WHO, 2021a). The large room, the small number of students and observing the prevention measures hygiene, keeping distance and wearing face masks would have allowed to perform face-to-face learning and teaching even during many weeks of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020/2021. Perhaps this encourages architects, administrations, teachers and students to vote for such places and to use them also during a pandemic that requires to keep distance. The "e"-part of blended learning, e-learning, is a wonderful tool, but it can not replace the experience and benefits of face-to-face learning and teaching. Together, in blended learning, they are strong (Bleimann, 2004; Paul & Jefferson, 2019; Todd et al., 2017).

The students – five in case 1 and eleven in case 2 – showed a high commitment, except one. The other fifteen were open for new learning approaches and showed willingness to participate and contribute. They were reliable, full of ideas and suggestions and showed a delightful sense of humour. The formative and summative evaluation gave insights, that the small number of students, the learning and teaching approach and the experience of the teacher in the fields social informatics and organization development plus the willingness of the students were crucial for the students' satisfaction. In their portfolios students described their satisfaction and learning success higher than in classical settings. Such a classical setting is for instance a seminar of two units per week combined with a weekly lecture series and a proof of performance at the end of a term (seminar paper, written or oral exam). One of the characteristics of the workshop series "Social Informatics" is the use of realistic scenarios. Learning in realistic scenarios is based upon the theory of cognitive learning: learning by insights and on a model empowers the learner, to explore a topic autonomously, to use scientific methods and to develop solutions. This enhances the learner's motivation and improves the learning outcome short-, middle- and long-term (Felder et al., 2000; Slavin, 1996).

The teacher, which is me, is a physician with a master degree in public health. I work as organization developer with companies and single clients. This facilitated to use theories, concepts and methods of organization development (OD) for the design, implementation and evaluation of the workshop series. OD is based on humanistic values, such as the well being of the individual, education and social responsibility (Argyris & Schön, 1978; Cooperrider et al., 2008; Cummings, 2008; DeMarco & Lister, 1999; Laloux, 2014; Senge, 2006; Sennett, 2012; Wiegers, 1996). This opens a way to respectful and, by the use of OD methods, effective and efficient cooperation of teacher and students on eye level. The workload of 1.5 hours per unit, including the face-2-face time, may seem low. This was possible because of experience (more than fifteen years as teacher, researcher, OD consultant and business coach) and a structured and well defined process plus – and especially important – the commitment and cooperation of the students. In my early teaching years the workload was higher. I am also a scientist. The research and development topics include web-based systems in health care, sociology and informatics, quality management in health care and also didactic and higher education. Thus I could perform a case study as participatory observant on the implementation of teaching social informatics. Other teachers surely will have different backgrounds. Mandatory are subject-specific, methodological and social skills. Useful is the willingness to see oneself as facilitator, mentor, guide and to appreciate the students (Cooperrider et al., 2008; Laloux, 2014; Senge, 2006; Sennett, 2012; Weßel & Spreckelsen, 2009; Wiegers, 1996).

Both the students and the teacher can be seen as "mirrors" of social informatics and its diversity. Different countries, educations, professions (including the students), age, gender, cultures, interests, characters and attitudes to life overall, work and learning. The setting as a workshop series, each of the eight lasting two days, with breaks of several weeks, in a comfortable seminar room offered time and space to develop and appreciate a productive learning and teaching experience.

So far some answers to the questions "How can the concepts of CM-PBL and agile learning and teaching transferred to a one-term-seminar-setting in social informatics?", "Does it work?", "How does it work?" and "Why does it work?" The conditions and context at HFU were 2017 and in the beginning of 2018 well suited for the implementation of such workshop series. Open minded professors and members of the university's administration supported the work of the visiting lecturer. Students are anyhow interested in such settings (Donnelly & Fitzmaurice, 2005; Felder et al., 2000; Merseth, 1991; Pape et al., 2002; Slavin, 1996; Weßel & Spreckelsen, 2009). And if not? This leads to the research question "What is necessary to make it happen?" What can teachers and other stakeholders in learning and teaching at universities do to make such settings happen beyond classical weekly flows? My answer as an organization developer is not strictly in scientific language: find stakeholders, who will support you, win students as allies and just go for it.

As I mentioned earlier: The purpose of the study "Social Informatics Experience" is to offer the reader an example and thus inspiration how students can learn social informatics holistically. The learning and teaching approach is not restricted to SI. It can be used for other topics and fields. The design of the seminar as workshop series, the data and the conclusion are intended to be used and perhaps useful in further research, decision making and application especially in the multi- and trans-disciplinary field of social informatics.

6 Conclusion and Outlook

The students' design of a study program in social informatics in case 1 (sub-section 4.8) shows, that these – and I suppose, other – students are aware of the multi-disciplinarity of social informatics and the needs to train in fields like informatics, economics, sociology and elective subjects.

These days the term social informatics is not widely known and sometimes misunderstood in science, in education and in society (Smutny 2016; Smutny & Vehovar, 2020). The misunderstanding refers to the field of the development of information technology in the area of welfare and social-service work, similar to health informatics and its applications. The low degree of familiarity may be caused by the fact that many scientists, practitioners and teachers work in one of the many fields of social informatics and name just their particular field like knowledge management, social media and world wide web or digitalization and other perspectives like ethics, law, economics and e-government. Smutny and Vehovar (2020) describe the situation as follows:

The problems with a common SI research denominator are all the more troublesome because SI addresses a broad area related to the interaction between society and information and communication technology (ICT), where many established disciplines already exist. On the other hand, there also appears to be a certain lack of conceptual grounding in some SI research, meaning it does not belong to any school of SI.

(Smutny & Vehovar 2020, p 529)

Furthermore SI is nowadays communicated with several terms, like "social informatics", "socio-informatics" (Stellenbosch University, 2021a & b) and "socioinformatics" (TU Kasierslautern, 2021). There is need to communicate social informatics and the variations of the term in science, in education, in the workplace and anywhere else, where it seems appropriate. Scientists, teachers and practitioners can draw the attention of stakeholders in social informatics – university administrations, policymakers in government, economics and elsewhere plus the public, represented for instance by journalists and media – to both the benefits of information technology and the jeopardies, for instance the misuse of social media (Darius & Stephany, 2020). The experiences with the COVID-19 pandemic show what information technology, sociology, psychology, philosophy (ethics) and social informatics can contribute to the mastering of a pandemic and other challenges.

Appendix A: Learning Concepts

A.1 Competency-based Learning (CBL)

Learning with hand, heart and mind – the stimulus and sense of haptic – is a well-tried and meanwhile science-based approach. More than two hundred years ago the pedagogue and educational reformer Heinrich Pestalozzi (1746–1827) developed substantial fundamentals in learning and education. The Verein «Pestalozzi im Internet» (2021) offers a comprehensive documentation and introduction to his work and life. Methods used in competency-based learning (CBL) build upon this approach.

Students need a comprehensive education in subject-specific, methodological and social competencies and skills. The purpose of CBL is to empower students to develop these skills (Jones et al., 2002). Dewey (1997 & 2008), Schön (1983), Argyris & Schön (1978 & 1995) and Biggs (2011) provided with their work basics for CBL: Dewey with experiential learning, Schön with the reflective practitioner, Argyris and Schön with theory in use and theory of action plus double loop learning, and Biggs with constructive alignment. Case- and project-based learning (PBL) use the theories and concepts of CBL (Donnelly & Fitzmaurice, 2005; Felder et al., 2000; Merseth, 1991; Pape et al., 2002). The approach is to learn in realistic scenarios.

Learning in realistic scenarios is based upon the theory of cognitive learning: learning by insights and on a model empowers the learner, to explore a topic autonomously, to use scientific methods and to develop solutions. This enhances the learner's motivation and improves the learning outcome short-, middle- and long-term (Felder et al., 2000; Slavin, 1996). Teachers envision themselves as facilitator, mentor, guide (Weßel & Spreckelsen, 2009). Braband and Andersen expressed this in their film "Teaching Teaching & Understanding Understanding" (2006).

A.2 Continued multidisciplinary project-based learning (CM-PBL)

In the nineteenth century problem-based learning was developed for law classes at Harvard University (Merseth, 1991). Realistic cases introduced the students to the topic and trained them on juristic thinking and decision making. Medical schools adapted this approach as problem-based learning, which was widely used from the 1970s on (Neufeld & Barrows, 1974; Van der Vleuten et al., 2004). Other fields, like computer science and economics, broadened the perspective and introduced project-based learning (Bleimann, 2004; Felder et al., 2000; Haux et al., 2004; Pape et al., 2002).

During a research and development project, that last from 2002 until 2007, with the focus on web-based information and mobile systems in health care Weßel & Spreckelsen (2009) introduced continued multidisciplinary project-based learning (CM-PBL). Students entered the research group to work on their thesis: student's research projects (similar to a bachelor thesis), diploma (similar to a master degree) and doctoral theses. Two scientists were co-teachers and supervisors. One of them performed the project management. The students developed in their theses parts of a web-based and several mobile systems, respective performed evaluations. The teachers also did research and development and thus both teachers and students proceeded with their scientific work. The project environment strengthened team identity and team work and improved students’ performance and research results. Furthermore the teachers' benefit was to train alternative teaching. The attitude to be a facilitator, mentor and guide for the students was fostered by the project setting and the structured cooperation of the two teachers in the formative assessment and support of the students. Based upon these experiences I use the CM-PBL-approach in several one and two term seminars since 2009. The necessary adaptation is facilitated by the use of agile learning and teaching methods.

A.3 Agile Learning and Teaching (ALT)

Focus on the customer and the development of a working product, appreciate staff and colleagues, work cooperative, flexible and swift. The concept of Agile Software Development offers values and principles to work in this way (Beck et al., 2001). Several agile methods were developed (Cohen et al., 2005). They could build upon previous evolutions (Larman & Basili, 2003). One of these is the holistic approach, that emerged during the 1980ies in product development, for which Takeuchi and Nonaka (1986) used the rugby-metaphor and introduced with it Scrum: the teams work as a whole to get the ball up the field, respectively to develop a product. Scrum is a move in rugby to restart the game.

Meanwhile agile approaches are also used as managing tools (Denning, 2018) and in education (Babb & Norbjerg, 2010; Layman et al., 2006). An "agile" seminar based upon the Scrum framework offers the students the opportunity to use the agile approach and to learn how to use it in their professional life. Weßel (2019, p. 141-146) describes the application.

Adapting Scrum has to consider five aspects:

- Teamwork: the teacher as team developer & formative evaluation

- Setting: workshops instead of 90-minutes-events

- Scrum translated: products, roles, artefacts and meetings

- Working products from the beginning on: the proofs of performance

- Final evaluation and acceptance

Students and teacher build a group. Group dynamics (Tuckmann, 1965; Tuckman & Jenssen, 1977) shows that to consider the steps forming, storming, norming, performing and adjourning helps to build a group and a team and to work efficiently, effectively and satisfying together. For the differentiation between group and team see (Levi, 2007, p. 4-6).

Such an approach is time consuming. Workshops, that last an afternoon, a day or two days and intervals of one, two or three weeks, afford to perform the five steps in group dynamics during each workshop and the whole term. During the workshops students can work on tasks in small groups and present and discuss the results with their peers. During the intervals the students can work on their proofs of performance and other tasks.

The formative evaluation can take place as warming-up at the beginning and wrap-up in the end of each day as check-in/check-out (Weßel, 2019, p. 226). Questions in Scrum are for instance: What did I do since yesterday? What will I do today? What inhibits me? Check-in/check-out serve to evaluate formatively the quality of the teacher's and students' work. This enables them to improve their work. Furthermore check-in/check-out can show how the students' and teacher's shape is (fitness, working load beside this seminar et cetera). For instance the teacher can ask "How did the last week go?" on the first day of a workshop in the morning. In the evening she can start the sentence: "Come to think of it …" Students and teacher stand in a circle (work in the room) and each student and then the teacher answer the question. This takes about five minutes with a number of five to fifteen students and one teacher. The findings of the check-in/check-out enable both teacher and students to adapt their work accordingly.

The first sentence of this section can be adapted to agile learning: as teacher focus on the students, as student focus on learning; as teacher produce high-end teaching, as student produce high-end proofs of performance; all: appreciate each other, work cooperative, flexible and swift.

The students work on proofs of performance in teams of two or three students. They write a paper concerning a small students' research project (in SI on topics such as smart city or digital dexterity). Another proof of performance is the creation of a portfolio that contains several reflections on topics like ethics and a description of the tasks the students work on during the workshops. The students present their progress in each workshop and get feedback from their peers and from the teacher. Milestones of the proofs of performance are: building the small team, finding and describing the topic, literature, development, final questions (to the peers and the teacher), delivery, review. Products, roles, artefacts and meetings in Scrum can be translated to agile learning.

- Products: the proofs of performance & exercises during and in between the workshops.

- Roles: teacher: scrum master (team developer) and product owner (reader of proofs of performance); students: developers (writing proofs of performance) and product owner (reading others' proofs of performance).

- Artefacts

-

- Vision: description of the proofs of performance

- Product backlog (requirements): learning objectives

- Sprint backlog (tasks): milestones; oral students' report on their progresses

- Burndown chart (done): documentation

- Impediment backlog (impediments): oral students' report on questions and impediments

- Product increment (software): the proceeding proofs of performance

Scrum inspired meetings during the term are

- Day 1: release planning: working approach, proofs of performance: groups and topics.

- Each following workshop: sprint (iteration-) planning and sprint review: see above, the milestones.

- Daily stand-up meeting: check-in/check-out on each workshop day.

- Last day: sprint retrospective: final reflection and evaluation.

The students deliver their proofs of performance two weeks ahead of the last workshop on the e-learning platform. The teacher annotates the students' files and delivers a review for each a few days ahead of the final workshop. Thus the group can perform a summative reflection and evaluation on the last day of the seminar. Three questions build the basis:

- What is your proof of performance about?

- What were your experiences during your work on it, as group and personally?

- The teacher's reviews: Where do you agree and where not? Why? Do you have further questions?

Finally the teacher sums up the learning and teaching and the work together and gives an outlook on future seminars. And then it is time for the social part of the adjourning period in the process of group dynamics: coffee and cake. The joint work of students on research projects and other tasks fosters the learning effects. The tools of blended learning support the work in between the face-to-face units.

A.4 Blended Learning (BL)

Blended learning consists of three parts, each of it with its significant meaning (Kerres, 2003; Weßel, 2019). Classroom learning (face-to-face learning) means, that students and teacher work together in one room. Methods include dialogue, group exercises and presentations, learning by teaching (a student becomes a teacher for a certain topic), scenario developments (students develop stories, games and movies). During self-study students explore a topic and engage themselves with it, alone and with peers. E-learning affords students' and teachers' use of platforms, clouds and communication tools for cooperation: communication, data and file storage, usage of libraries, for instance books, papers, films, et cetera. The COVID-19 pandemic, which started in January 2020, required the restriction of classroom learning as one means of the preventive measure "keeping physical distance" (WHO, 2021b). Nevertheless nothing can replace personal contact in learning, working and other social encounters (Bleimann, 2004; Paul & Jefferson, 2019; Todd et al., 2017).

Appendix B: Organization Development in Learning and Teaching

Organization Development (OD) deals with the cooperation of people in companies, administrations, universities, schools, hospitals, associations, unions, political and other organizations. OD is based on theories, insights and methods from sociology, psychology, economics and didactic. The goal and purpose of OD is to pilot change for the well being of both the organization and the people inside and beyond (Argyris & Schön, 1978; Cooperrider et al., 2008; Cummings, 2008; DeMarco & Lister, 1999; Laloux, 2014; Senge, 2006; Sennett, 2012; Wiegers, 1996).

OD can be applied transorganizational, organizational, in a department, in projects and other settings, where ever people act together. OD came into being during the 1940ies and 1950ies. It is based upon humanistic values, such as the well being of the individual, education and social responsibility. The approach is systemic. This means, to see the environment and parts of it as complex constructs, that are in turn parts of other complex constructs. Broadly speaking OD assumes that an organization prospers if the people in this organization prosper. The top management and consecutive the management and the staff are together in charge to make it happen. This is a perpetual endeavour. "Prosper" includes for the organization economical, social and ecological success, regardless whether it is a production or service company, a profit oriented company or a non-profit institution, an administration or anything else. "Prosper" means for people health, appreciation, comfort, satisfying and demanding but not overwhelming work, the opportunity to develop personally and one's career plus a proper salary. Transferred to the implementation of a seminar this means, that a teacher as the OD manager in charge adopts this attitude and integrates students – the OD staff – and the administration of the university and colleagues – OD staff and management – into the design, planning, management and realization process of a particular seminar. The students' salary is their learning, success and certificate.

Appendix C: Social Informatics Curriculum

The curriculum for the workshop series Social Informatics is available for students and the public in German since 2017 and also in English since December 2021 (Weßel, 2018). The following names the pages, their URL and gives for each a short introduction.

Social Informatics

https://www.tosaam.de/seminar/social-informatics/

This builds the introduction to the field, the target audience and purpose of education in social informatics (SI), an overview on contents and learning objectives and a definition of SI.

SI | Questions

https://www.tosaam.de/seminar/social-informatics/si-questions/

This contains the questions that led to the identification of the workshop topics, considering and integrating the requirements and contents, the university had included in the description of the modules. The page starts with

Questions are the strongest tools in research, development and learning. To answer the question "What is Social Informatics?" answers to further question can be helpful, to draft and perform R&D and learning & teaching, for instance the SI workshop series, described on these pages.

The page continues with the questions, overall forty-one.

SI | Workshop Series

https://www.tosaam.de/seminar/social-informatics/si-workshopseries/

This describes in short the field of SI applied in the field of IT product management, because the workshops series was part of the study path on SI in the bachelor program "IT product management" at HFU. It continues with an introduction to the learning objective and the learning and teaching methods.

SI | content and learning objectives

https://www.tosaam.de/seminar/social-informatics/si-content/

The workshop series merge the two modules "information technology and its social context" and "social nets". This page lists the contents (topics), the learning objectives and the proofs of performance.

SI | sequence – summer term 2017

https://www.tosaam.de/seminar/social-informatics/si-summer2017/

This gives an overview on the workshop series, the documentation, and how content and learning objectives are connected. The description of each of the eight workshop follows with date, topics, milestone of the proofs of performance and – where applicable – students' tasks up to the following workshop.

The eight workshops are

- Getting started: Social net and electronic media.

- Exploration and evaluation: What do the users need?

- Internationalization and globalization: Life is a net.

- Product management and ethics: The art of balance between the technically feasible and social consequences.

- Life world and work world: In fact I live while I work.

- Hackathon: Let's work … and have fun.

- Digital Dexterity and Internet of Things: About handling the new.

- Synopsis: It's all about communication.

SI | sequence – winter term 2017/2018

https://www.tosaam.de/seminar/social-informatics/si-winter2017/

This is analogical to "summer term 2017".

SI | proofs of performance

https://www.tosaam.de/seminar/social-informatics/si-proofs/

For the module "information technology and its social context" the proof of performance is a portfolio. For module "social nets" it is a students' research project in small groups. This page offers links to the assessment criteria and explains the submission procedure to be followed by the students. Furthermore it gives recommendations how to approach the proofs of performance.

SI | portfolio

https://www.tosaam.de/seminar/social-informatics/si-portfolio/

This page describes in detail, what the purpose of a portfolio is, how the students work on it, the learning objectives, the review process and the assessment criteria.

SI | students' research project (SRP)

SI | Literature

https://www.tosaam.de/seminar/social-informatics/si-literature/

This names the literature recommended by the teacher.

Appendix D: Proofs of Performance

The students worked on proofs of performance in teams of two or three students. The proofs are related to the primordially two modules, that were merged in the workshop series. For "Soziale Netze" (social nets) the students wrote a paper concerning a small students' research project on topics such as smart city or digital dexterity. The paper comprised about ten pages per person (this is twenty to thirty pages +/- ten percent) plus cover, table of contents, abbreviations, figures, references and – if the authors decide to include them – glossary or alphabetical index. One page covers about 1500 characters including blanks. The proof of performance for "Informatik im sozialen Kontext" (information technology and its social context) was the creation of a portfolio. It had to contain several reflections on topics like ethics and a description of the tasks the students worked on during the workshops. The portfolio comprised at least twenty pages plus cover et cetera (see above). For the students and other interested readers I described the SRP and the portfolio in the blog entry of February 24, 2017, and in the online curriculum on sub-page "proofs" (Weßel, 2018):

Students' research project (SRP):

In information technology and other areas you develop products and services following the steps analysis, design, implementation and evaluation. Design a draft for the development and implementation of a digital social network of a company. Or: Design a draft for for the marketing of a product or a service. Use the 8+1 W. Include in the design a network analysis. Use methods of qualitative field research and software-engineering including agile methods. Take into account social conditions, that have an impact, for instance historical, political, cultural, economical and media driven aspects.

Work during the term on a portfolio:

a) write a reflection on a number of topics due to targeted days,

b) assemble your work done during the workshops (visualisations and others),

c) introduce your students' research project in the module "social nets": (co-)authors, title and abstract,

and find a peer, with whom you cooperate as buddy team: you will present the reflections [in (a)] of your buddy to the course and enter a dialogue.

The students presented their progress in each workshop and got feedback from their peers and from me, the teacher. Milestones of the proofs of performance are: building the small team, finding and describing the topic, literature, development, final questions (to the peers and the teacher), delivery and review. We, students and teacher, worked together using the approach of Agile Learning and Teaching (see Appendix A.3 for more details).

References

- Ammenwerth, E., Iller, C., & Mansmann, U. (2003). Can evaluation studies benefit from triangulation? A case study. International journal of medical informatics, 70(2-3), 237-248.

- Argyris, C., & Schön, D. (1978). Organizational Learning: A theory of action perspective. Addison Wesley.

- Argyris, C., & Schön, D. (1995). Organizational Learning II: Theory, Method, and Practice. FT Press.

- Babb, J., & Norbjerg, J. (2010). A Model for Reflective Learning in Small Shop Agile Development. In: J. Molka Danielsen, H. Nicolajsen, & J. Persson JS (Eds). Information Systems Research Seminar in Scandinavia Nr. 1: IRIS 33. (pp. 23-38). tapir akademisk forlag.

- Beck, K., Mike Beedle, M., van Bennekum, A., Cockburn, A., Cunningham, W., Fowler, M., Grenning, J., Highsmith, J., Hunt, A., Jeffries, R., Kern, J., Marick, B., Martin, R., Mellor, S., Ken Schwaber, K., Sutherland, J., & Thomas, D. (2001). Manifesto for Agile Software Development – The Mainfesto – Principles – History. Retrieved July 17, 2021, from http://agilemanifesto.org/

- Biggs, J., & Tang, C (2011). Teaching for Quality Learning at University. 4th edition. Open University Press.

- Bleimann, U. (2004). Atlantis University – A New Pedagogical Approach beyond E-Learning. In: S. Furmell & P. Dowland (Eds.), Proceedings of the Fourth International Network Conference (INC 2004). University of Plymouth School Of Computing, Communications And Electronics.

- Brabrand, C., & Andersen, J. (2006). "Teaching Teaching & Understanding Understanding" 19 minute award-winning short-film about Constructive Alignment. University of Aarhus, Denmark. Retrieved Dec 14, 2021, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iMZA80XpP6Y (1/3) & https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SfloUd3eO_M (2/3) & https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=w6rx-GBBwVg (3/3)

- Buonanno, G., Stabile, L., & Morawska, L. (2020). Estimation of airborne viral emission: quanta emission rate of SARS-CoV-2 for infection risk assessment. Environment International, 141, 105794. Retrieved Dec 14, 2021, from https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2020.105794

- Cohen, D., Lindvall, M., & Costa, P. (2004). An introduction to agile methods. Advances in Computers, 62(03), 1-66.

- Cooperrider, D., Whitney, D., & Stavros, J. (2008). Appreciative Inquiry Handbook. 2nd edition. Berrett-Koehler Publishers.